Task Management

Andrey Shcherbina

Mar 12, 2025

Every second, our brain is bombarded with an avalanche of sensory data. Sounds, images, smells, tactile sensations—the volume of information is so enormous that it's impossible to process everything. To cope with this flow, our brain has evolved and developed a mechanism of selective attention—the ability to focus on significant stimuli and ignore everything else.

Selective attention acts as an invisible filter, determining what enters our consciousness and what remains unnoticed. In the era of information noise, this property of our psyche becomes both our salvation and limitation. Understanding how this mechanism works provides the key to more effective communication and decision-making in both personal life and professional environments.

Scientific Explanation of Selective Attention

The phenomenon of selective attention has been studied by scientists for decades. One of the first was Donald Broadbent's filter model (1958), which suggested that our brain blocks irrelevant information at an early stage of processing. Later, Anne Treisman proposed the attenuation theory, according to which filtering occurs not on an "all or nothing" principle, but rather with signal weakening for less important stimuli.

Modern neurobiologists have found that selective attention is associated with activity in the prefrontal cortex and parietal lobe of the brain. Using functional MRI, researchers observe how the brain literally "highlights" certain areas of the sensory cortex, enhancing the processing of selected information and suppressing the response to distracting factors.

This process can be compared to tuning a radio: to hear one station, the receiver must amplify the desired frequency and filter out all others. In our brain, the role of such a tuner is performed by neuromodulators—substances that strengthen or weaken signals between neurons, thus regulating the "volume" of various information channels.

7 Classic Examples of Selective Attention

Selective attention manifests in everyday life constantly, although we rarely realize it. Scientists have developed many experiments that clearly demonstrate the operation of this mechanism and its impact on our perception. Let's consider the most famous and illustrative examples.

Example | What It Demonstrates | Researchers | Practical Significance |

Cocktail Party Effect | Ability to focus on one sound source and automatically respond to significant stimuli | Colin Cherry (1953) | Explains selective perception in conditions of information noise |

Invisible Gorilla | Inattentional blindness when concentrating on a task | Simons and Chabris (1999) | Shows how we can miss obvious events when focusing on a specific task |

Stroop Effect | Cognitive conflict between automatic and controlled processes | John Ridley Stroop (1935) | Demonstrates the difficulty of switching between conflicting stimuli |

Banner Blindness | Ignoring predictable interface elements | Benway and Lane (1998) | Affects interface design and advertising effectiveness |

Change Blindness | Inability to notice changes in a scene | Rensink, O'Regan, and Clark (1997) | Shows intermittent updating of our mental model of the world |

Selective Listening | Filtering of audio information | Broadbent (1958) | Explains difficulties with multitasking when perceiving information |

Blue Bear Effect | Thought suppression paradox | Daniel Wegner (1987) | Demonstrates the complexity of deliberately ignoring information |

1. Cocktail Party Effect

Imagine a noisy party where dozens of conversations are happening simultaneously. Despite the cacophony of sounds, you can focus on the conversation with your interlocutor, effectively filtering out other voices. However, if someone at the other end of the room mentions your name, you're likely to hear it. This phenomenon was first described by Colin Cherry in 1953.

The cocktail party effect demonstrates two important aspects of selective attention: the ability to focus on a specific sound source amidst noise and the automatic switching of attention to personally significant stimuli. Experiments have shown that people can track the content of only one conversation, but the brain continues monitoring the environment for important signals.

In a business context, this explains why participants in lengthy meetings may "disconnect" from the discussion but instantly return to the conversation when their name is called or their project is mentioned.

2. The Invisible Gorilla Test

One of the most famous experiments on selective attention was conducted by psychologists Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris in 1999. Participants were shown a video in which two teams (in white and black shirts) passed a basketball to each other. The task was to count the number of passes made by the team in white.

In the middle of the video, a person in a gorilla costume walked across the court, stopped in the center, beat their chest, and left. Surprisingly, about 50% of the experiment participants did not notice the gorilla, being completely focused on counting passes. This phenomenon was named "inattentional blindness."

This example shows how selective our attention can be, and how we can completely miss unexpected events if our brain is occupied with a specific task. In the professional sphere, this can lead to missing important opportunities or ignoring warning signals if they are not within the predetermined focus of attention.

3. The Stroop Effect

Try to quickly name the color of the font in which the following words are written: GREEN, RED, BLUE, YELLOW. If the word "RED" is written in blue, most people take longer to name the color (blue), overcoming the automatic tendency to read the word itself (red).

The Stroop effect, named after psychologist John Ridley Stroop, demonstrates a cognitive conflict between automatic and controlled attention processes. Reading words is such an automated skill that it requires additional effort to switch attention to the font color.

This phenomenon shows how strongly habitual attention patterns influence us and how difficult it can be to consciously redirect focus even with obvious information conflict. In a work environment, similar cognitive conflict can arise when there is a need to revise established processes or adapt to new working methods.

4. Banner Blindness

If you've ever browsed a web page and not noticed the advertisements placed on it, you've experienced "banner blindness." Research shows that internet users have learned to automatically ignore areas of pages where advertisements are usually placed, without even realizing it.

Eye-tracking studies confirm that users' gaze literally bypasses advertising blocks, forming a so-called F-pattern for scanning the page. This mechanism developed as a protective reaction to information overload in the online environment.

Banner blindness illustrates how our selective attention can adapt to repetitive patterns and automatically filter what we consider unimportant. For businesses, this means that critically important information should be presented in a format that won't be automatically filtered out due to similarity with frequently ignored content.

5. Change Blindness

In change blindness experiments, participants are shown two almost identical pictures alternately, with a brief interruption between them. Despite obvious changes (such as the disappearance of a large object), many people cannot notice them even after multiple viewings.

A classic experiment by Daniel Simons demonstrates this phenomenon in real life: a researcher on the street asked a passerby for directions, and during the conversation, a door was carried between them, behind which the interlocutor was replaced. Surprisingly, about 50% of people did not notice that they were now talking to a completely different person.

Change blindness shows that our perception of continuity is much more fragile than it seems. We don't register every frame of reality, but rather create a general model of the situation, which we update only with significant changes. In a business context, this can lead to unnoticed gradual changes in market trends or customer behavior.

6. Selective Listening

Classical experiments with dichotic listening, when different messages are simultaneously delivered to the left and right ears, show how selective our perception of audio information can be. Participants who were instructed to follow the message in one ear often could not even determine the language of the message delivered to the other ear.

Interestingly, if the untracked channel contained emotionally significant words (e.g., the person's name) or switched to the same voice as in the tracked channel, the listener's attention sometimes switched. This shows that filtering is not absolute, and some preliminary analysis of all incoming information is still carried out.

In the context of business meetings, selective listening explains why participants may miss important details of the discussion, especially if they are simultaneously checking email or working with documents. Our brain is simply not capable of effectively processing parallel streams of complex verbal information.

7. The Blue Bear Effect

Try not to think about a blue bear for a minute. Paradoxically, the very instruction to ignore a certain thought increases the likelihood of its occurrence. This phenomenon, described by psychologist Daniel Wegner, demonstrates the paradoxical side of selective attention.

Research shows that attempts to suppress unwanted thoughts often lead to a "rebound effect"—strengthening these thoughts after a period of suppression. This mechanism explains why it's so difficult not to think about problems before sleep or why we often return to topics we try to avoid.

The blue bear effect has important implications for communication and management. For example, the instruction "don't worry about possible problems" may actually increase anxiety, and attempts to avoid certain topics in teamwork may paradoxically lead to fixation on them.

Selective Attention in the Work Environment

Think back to your last important meeting. Did you notice how some participants only perked up when their projects were mentioned? How often have you caught yourself checking emails during an online conference, missing crucial details of the discussion?

In today's office environment, our attention is constantly tested. We're interrupted every 8 minutes—a call, a message, a colleague with a question. After each switch, it takes us an average of 15-20 minutes to fully return to the task. Nearly a quarter of our workday is spent simply regaining concentration!

Business meetings have become a perfect showcase for selective attention. Picture this: the marketer latches onto mentions of the advertising campaign, the developer mentally edits code when hearing about technical tasks, and the sales manager only becomes animated when discussing quarterly figures. Everyone filters the information stream through the lens of their own responsibilities, unwittingly missing what might be critically important for the project as a whole.

The situation is compounded by our love for multitasking. We convince ourselves that we can effectively listen to a presentation while responding to emails. But our brain doesn't work that way—instead of parallel processing, it's forced to constantly switch, losing pieces of information with each transition.

This is especially noticeable in lengthy Zoom meetings, which have become the norm since the pandemic. Without the energy of personal communication and direct contact, our attention depletes faster. We begin filtering information even more selectively, often without realizing it. As a result, after an hour-long meeting, colleagues frequently leave with completely different understandings of what was agreed upon and what tasks lie ahead of them.

Strategies to Overcome Selective Attention Limitations

Understanding the mechanisms of selective attention allows developing effective strategies to minimize its negative effects. Rather than fighting the brain's natural limitations, it's more productive to adapt work processes taking these features into account.

Here are key strategies that have proven effective:

Mindfulness practices — Regular meditation strengthens the activity of the prefrontal cortex responsible for attention regulation. Research shows that even an 8-week mindfulness program significantly improves concentration.

Information structuring — Helps the brain allocate attention resources more efficiently:

Using visual elements instead of solid text

Grouping related ideas into logical blocks

Highlighting key points with color or formatting

Periodically summarizing long discussions

"Deep work" strategy (Cal Newport) — Allocating time blocks for concentration on one complex task without switching, which counteracts attention fragmentation.

Information environment management:

Turning off notifications during concentrated work

Creating a physical space with minimal distractions

Using information filtering tools

Planning regular "information detoxes"

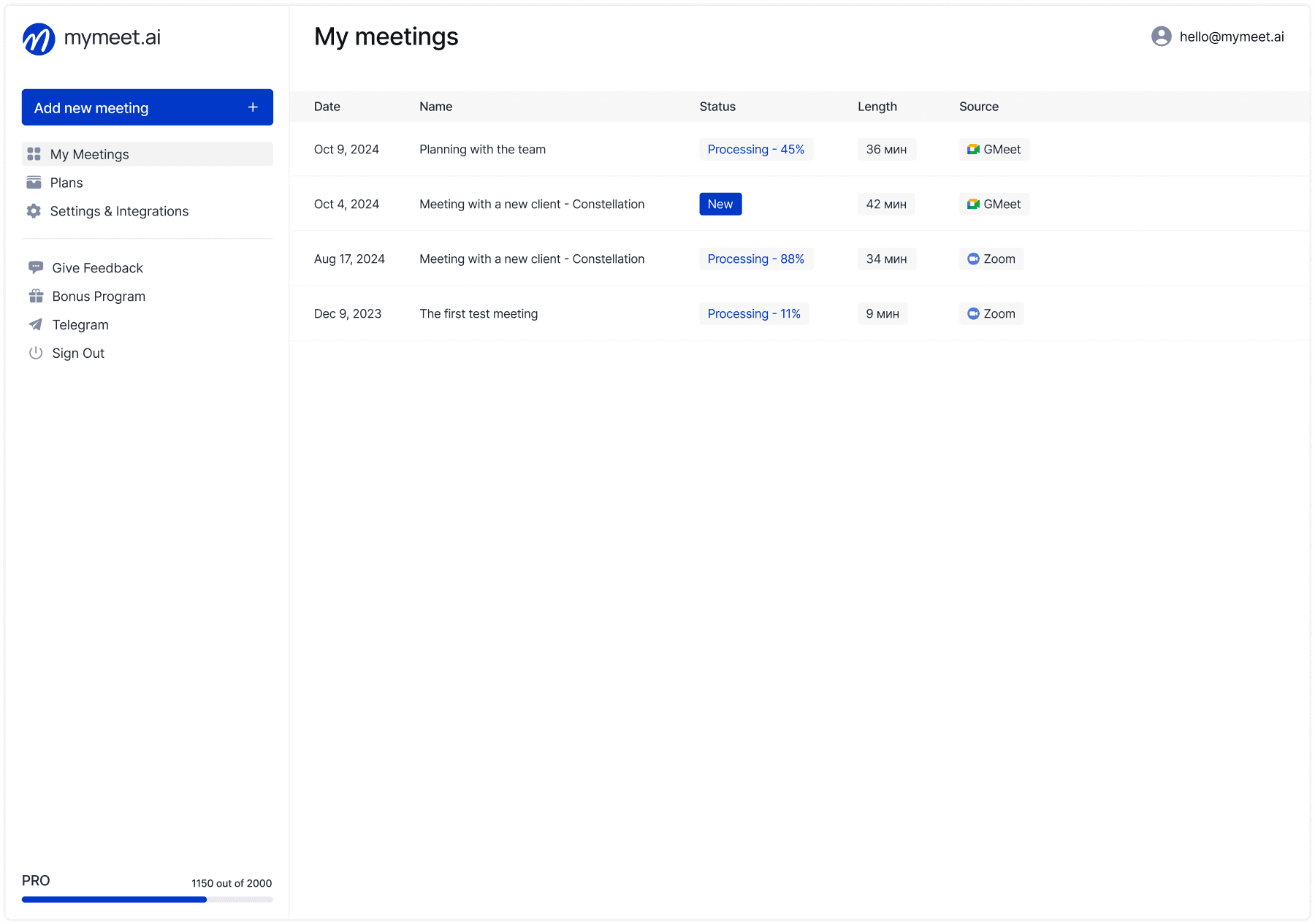

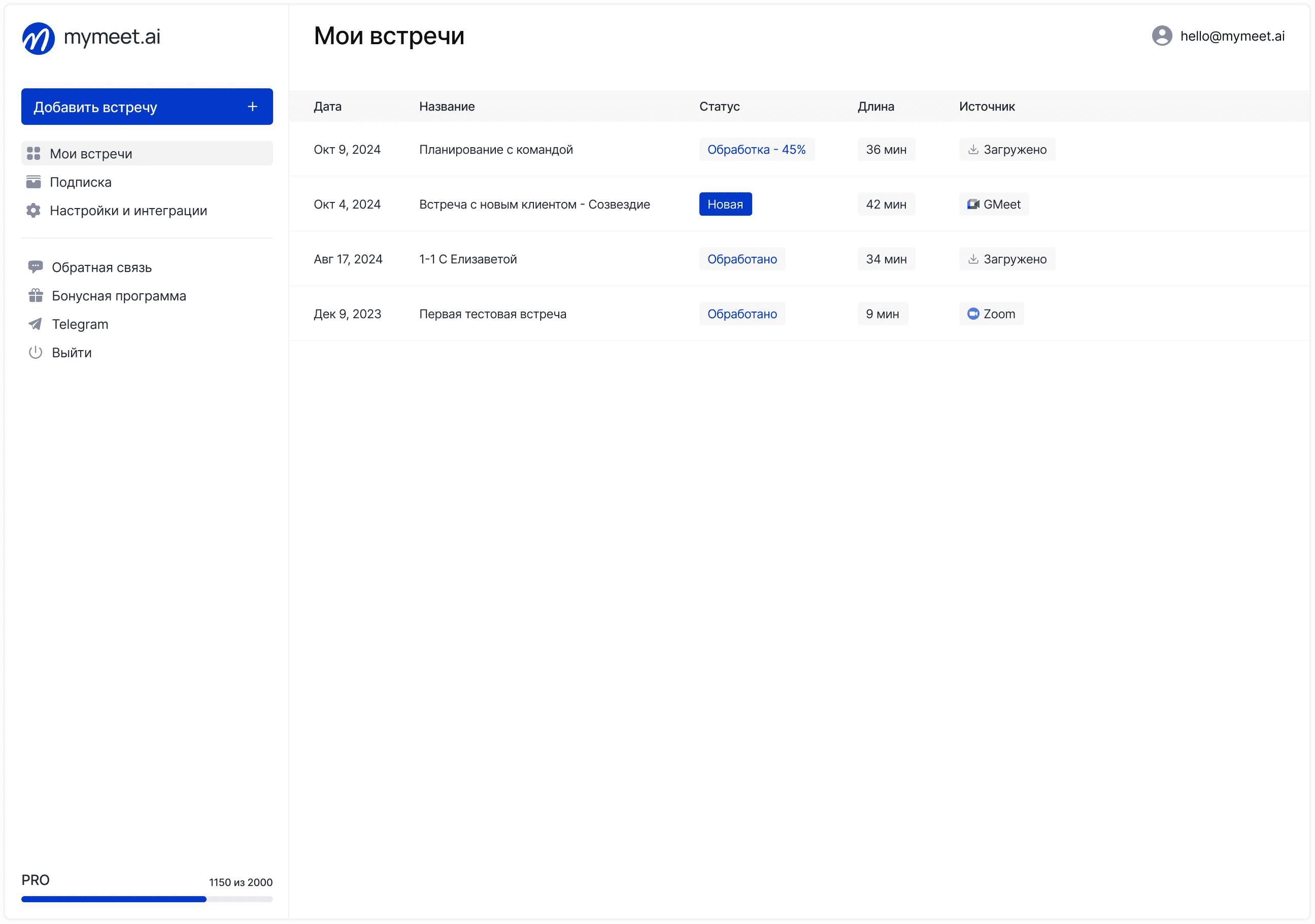

How mymeet.ai Helps Overcome Selective Attention Limitations

In the era of information overload, technological solutions become a necessary complement to cognitive strategies. AI assistants specializing in communication analysis can significantly compensate for the limitations of human attention, especially in the context of business meetings.

The mymeet.ai platform is designed specifically to address the problems associated with selective attention during business communications. Working as a "second brain" for the participant, the AI assistant processes 100% of the information, not subject to the limitations inherent in human perception.

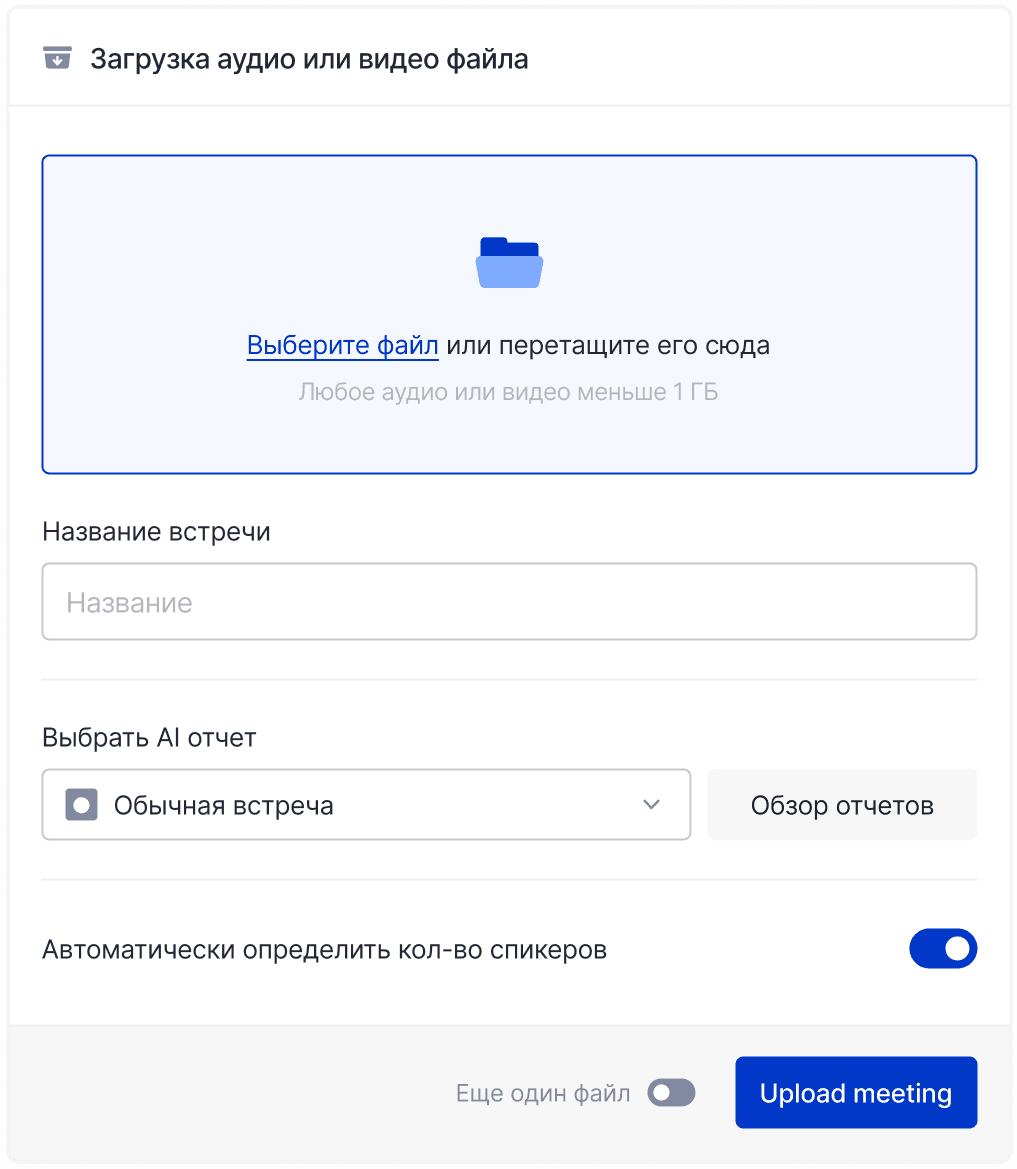

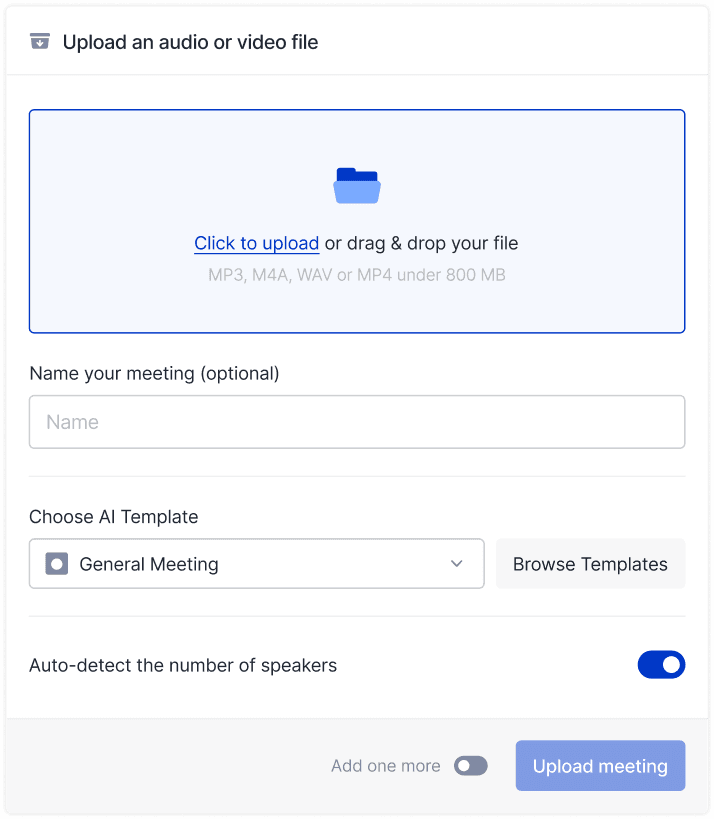

Automatic recording and transcription of the meeting with speaker separation ensures complete capturing of content, including details that participants might miss due to selective attention. Particularly valuable is the function of dividing the transcript into semantic chapters, which helps structure information for better perception.

AI analysis identifies key discussion points, agreements, and assigned tasks, highlighting them from the general information flow. This is especially important considering that meeting participants often leave with different understandings of the agreements reached precisely because of selective perception.

The AI chat function allows asking specific questions about the meeting's content afterward: "What upselling strategies were discussed?", "What deadlines were set for the project?". This compensates for the natural human tendency to focus only on the information that corresponds to their priorities.

Integration with popular meeting tools (Zoom, Google Meet, Yandex.Telemost) and CRM systems (e.g., amoCRM) allows seamlessly incorporating this intelligent tool into existing work processes, creating a seamless user experience.

Practical Exercises for Attention Training

Although technological solutions significantly help compensate for attention limitations, developing one's own cognitive skills remains an important task for professionals in any field. Here are effective exercises for training selective attention:

Pomodoro Technique

Divide work into 25-minute concentration sessions

Take short 5-minute breaks between sessions

After 4 cycles, take a long break (15-30 minutes)

Goal: Training the ability to maintain focus without distractions

Mindfulness Meditation

"One breath, one thought" exercise (5-10 minutes daily)

"Body scanning" practice for developing sensory attention

Technique of "observing thoughts" without engaging with them

Result: Improved metacognitive skills and awareness

Cognitive Training

N-back tasks – tracking information presented n steps back

Games for finding differences between similar images

Exercises for switching between tasks according to a specific rule

Mobile applications with adaptive difficulty levels

Communication Exercises

Active listening practice with paraphrasing key points

"Mirror" exercise – exact repetition of the interlocutor's phrase

"Detailed retelling" technique – reproducing information with maximum accuracy

Expanding Perceptual Abilities

Working with 3D stereograms for peripheral vision training

Exercises for simultaneous perception of multiple stimuli

"Five senses" training – sequential focusing on different sensory channels

Conclusion

Selective attention is a fundamental property of our cognitive system that helps us function in a world of information overload. However, the same mechanisms that protect us from the chaos of sensory stimuli can create serious limitations, especially in a professional environment.

Examples of selective attention, from the cocktail party effect to the invisible gorilla test, clearly show how selective our perception can be and what important information we may miss, even when it's right in front of us.

Combining cognitive strategies and modern technological solutions creates a powerful arsenal for overcoming these limitations. Mindfulness practices and purposeful attention management, combined with AI assistants such as mymeet.ai, significantly improve the quality of information processing.

In a world where information has become both the most valuable resource and a source of overload, the ability to effectively manage one's attention is becoming a critical skill. Understanding the mechanisms of selective attention and implementing strategies to compensate for its limitations is a key step toward improving communication effectiveness and decision-making.

Frequently Asked Questions About Selective Attention

Can the ability to concentrate attention be improved?

Yes, attention can be trained. Effective methods include regular meditation (15 minutes daily), cognitive exercises (e.g., n-back tasks), physical activity, and deep work practice without multitasking. Research shows a 30% improvement in concentration after 8 weeks of systematic training.

How does age affect selective attention?

With age, the ability to filter irrelevant information and quickly switch between tasks decreases. However, older people often compensate for this with better strategies for allocating attention resources and experience. Regular cognitive activity and physical exercise slow down the age-related decline of these functions.

Why do we notice our name in a noisy room?

The brain constantly analyzes all incoming information in the background and automatically increases processing priority for personally significant stimuli. One's own name activates specific neural networks even without conscious attention, allowing us to "pick it out" from the general noise background of conversations.

How does stress affect selective attention?

Stress causes "tunnel vision"—narrowing the focus of attention on potential threats while ignoring peripheral information. Short-term stress can improve concentration, but chronic stress depletes attention resources, reduces cognitive performance, and impairs the ability to filter distractions.

What are the advantages of artificial intelligence in overcoming attention limitations?

AI is not subject to fatigue, selective perception, or cognitive biases. Systems like mymeet.ai process 100% of meeting information, ensuring complete content capture and highlighting key points. AI structures large volumes of data in a format optimal for human perception, compensating for the natural limitations of our attention.

Andrey Shcherbina

Mar 12, 2025